Reviewing Poland-Ukraine relations throughout history

My Polish grandmother was from Krakow (Western Galicia) and survived WW2, which included Nazi German invasion and occupation, followed by Soviet Russian "liberation" and occupation (which involved lots of looting, rape, and senseless destruction). But surprisingly, her most horrific war stories involved Ukrainian Nationalists and how they massacred Polish people—mostly women and children—in Eastern Galicia.

Over half a century later, I've never experienced any tension or bad feelings with any of the Ukrainians I've met in my life, and I found it easy to get along with Ukrainians due to our shared culture and even some similarities in our languages. So when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2014 and then again in 2022, I was happy to see Poland quickly welcome Ukrainian refugees and provide military aid, and I have been rooting for Ukraine to win the war.

However, my Grandmother's war stories are still sometimes in the back of my head, and I can't help but wonder if accepting millions of Ukraine refugees will backfire on our country in the future. To resolve these thoughts, I started to read more about Poland's and Ukraine's shared history. Here's what I learned...

Overview

Living Ironically In Europe has a nice 3 minute overview, but misses many important events and is not accurate in how "unified" Poland and Ukraine were against Russian domination. This is a misconception that I, too, had before reading the history.

Shared Origins (5th century)

The legend of Lech, Czech, and Rus tells the story of three brothers—Slavic chieftains—who went on a hunting trip looking for new lands to settle:

- Czech traveled west, settled in the hilly countryside of Bohemia, and founded the Czech nation.

- Lech traveled north, settled on a vast plain, and founded the Polish nation.

- Rus traveled east and founded the Kyivan Rus (modern-day Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus).

Medieval Rivalries (10th–14th centuries)

During medieval times, Poland and Kyivan Rus (the precursor to modern Ukraine) were neighbouring kingdoms with fluctuating relations. Poland attempted to expand eastward, while the Kyivan Rus’ attempted to expand westward. The Kyivan Rus's western-most territories were Galicia and Volhynia. Then the Mongols came...

In the 1240s, Mongol invasions wiped out much of the Kyivan Rus, including the main city of Kyiv. Some Polish cities were also raided and destroyed, but Poland avoided getting conquered and occupied.

After the Mongol invasions, Galicia and Volhynia became a semi-independent vassal state of the Mongols and sought alliances with Poland and Hungary to resist Mongol influence.

In the 14th century, the ruler of Galicia-Volhynia, Yuri II Boleslav, was poisoned by Ruthenian (Ukrainian) nobles and died with no heirs. This sparked a succession crisis.

- Galicia became part of Poland after successful battles against the Mongols and Ukrainian nobles.

- Volhynia became part of Lithuania after a peace treaty with Poland.

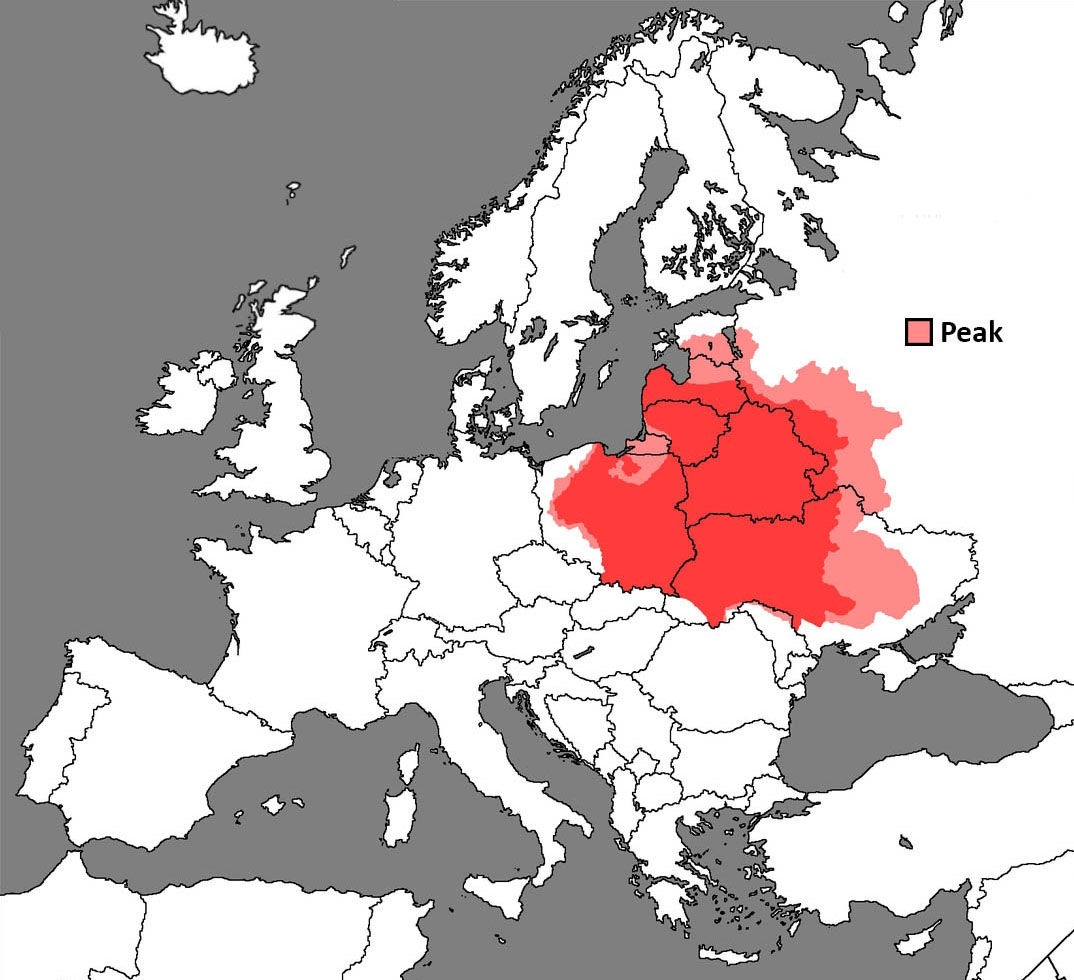

Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth (16th–18th centuries)

In 1569, Poland and Lithuania formed a commonwealth with the Union of Lublin agreement.

Lithuania transferred many of the Ruthenian (Ukrainian) territories it controlled, including Volhynia (Wołyń), to Polish rule. These territories had a large number of Ukrainian peasants, a small Ukrainian nobility, and the Cossacks. The Cossacks were a semi-nomadic, militarized society of Ukrainian outcasts and anarchists.

How did Polish nobility manage to mess up ruling over these new territories?

Religious Persecution

Officially, the commonwealth guaranteed freedom of religion as per the Warsaw Confederation of 1573. However, there was still lots of social pressure on Ukrainians to convert to Roman Catholicism. As an atheist from Poland, I can sympathize with the frustration Ukrainians would have had with Catholic pushiness about religion.

Ukrainian nobles were the most open to conversion, as they had the greatest financial incentives to do so. The Ostrogski and Wisniowiecki families were good examples. In contrast, Ukrainian peasants and Cossacks were much more firm in their beliefs and unwilling to give them up (and rightfully so).

Between 1588 and 1596, efforts were made to reunite the Ukrainian Orthodox Church with the Roman Catholic Church. This resulted in the Union of Brest agreement and the formation of the Greek Catholic Church, to which Orthodox Ukrainians were expected to convert. The Cossacks, in particular, were strongly opposed to this, and Polish nobles and clergy made things worse by engaging in religious persecution:

- Orthodox churches were converted to Greek Catholic churches.

- Orthodox believers who refused to follow the new church faced legal discrimination.

- Orthodox bishops who resisted the new church were imprisoned or expelled.

Consequences: Catholic fanatics in Poland would lead to the downfall of the commonwealth by deepening religious divisions, fueling uprisings and massacres, and strengthening Russian influence as many Orthodox looked to Moscow for protection.

Mistreatment of Peasants

Life for peasants/serfs in Poland was harsh.

Regardless if they were Ukrainian or Polish...

- Serfs were legally bound to the land and could not leave without the permission of their noble landlords.

- Serfs had to perform unpaid work for the nobles, leaving little time for serfs to work their own land.

- Serfs had to pay most of the taxes; nobles were mostly tax-exempt.

- Serfs had no political representation; nobles got to elect the king.

- Serfs could not testify against a noble in court.

- Nobles had almost absolute power over serfs and little accountability.

Conditions were even worse for serfs in Ukrainian lands because many nobles didn't want to live there, so instead, they would lease the land to arendators for a share of the profit. Ardentors were often Jewish, which further angered Ukrainians. For example, Khmelnytsky, during his uprising, would tell Ukranians that the Poles had sold them as slaves "into the hands of the accursed Jews."

Nobles also passed ridiculous propination laws, which meant that serfs could only buy alcohol from their noble or their noble's ardentors. But the craziest part is that serfs had a minimum quota of alcohol that they HAD to buy. This became one of the main causes of alcoholism among serfs.

So, not surprisingly, some serfs would flee to the borderlands to join the "free people" (Cossacks). If I were a serf back then, I'd probably want to join the Cossacks, too.

Mismanagement of Cossacks

Poland had a love-hate relationship with the Cossacks. Poland formally recognized and hired some Cossacks as "Registered Cossacks", which meant they would get yearly salaries, legal rights similar to lower nobility, tax-free status, and exemption from serfdom. In exchange for this, the Registered Cossacks would help keep unregistered Cossacks under control and would protect Poland's borders from Tatars (who frequently raided Ukraine and Poland for slaves), Ottomans, and Muscovites (Russians).

The number of Registered Cossacks was initially 3,000, then later it mostly fluctuated between 6,000 and 8,000. The issue was that the number of unregistered Cossacks was always multiple times higher than the number of Registered Cossacks, and a recurring request/demand from Cossacks would be to increase the registration numbers. However, the salaries of Registered Cossacks would be costly for the Polish state to maintain, and Polish nobles were also concerned about not making Cossacks too powerful and not incentivizing peasants to escape from serfdom.

Other Cossack demands included...

- Protections for unregistered Cossacks. (Seems fair.)

- Political representation in parliament for Cossacks. (Seems fair.)

- Equal rights for Orthodox clergy and the return of Orthodox churches that were given to Greek Catholics. (Seems fair.)

- Limiting the power of Polish landlords and middlemen. (Seems fair.)

- Freedom to wage raids against the Ottomans and Tatars whenever they want to. (This would directly conflict with peace treaties that Poland had with the Ottomans.)

I think many of these demands were fair, and it's sad to see that our Polish nobility couldn't make a reasonable compromise. It would have been far less costly than what would follow.

In 1591, the first Cossack uprising took place. It was started over a land dispute between a Cossack noble, Krzysztof Kosiński, and a Catholic-Ukrainian noble, Janusz Ostrogski. Kosiński felt wronged and started a series of attacks on the noble's city and estates, which inspired other Cossacks and peasants to rebel as well.

Cossack uprisings would become a regular occurrence throughout the commonwealth's history.

In 1648, the largest and longest uprising was started and led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky, a Ukrainian noble who became a Cossack. He was radicalized when the heir of a Polish noble he fought for tried to seize his lands. He traveled twice to Warsaw to ask the King for help but found the King unable/unwilling to do much (Polish kings were elected by Polish nobility). So when he couldn't get justice, he turned to rebellion.

Highlights from the Khmelnytsky Uprising

- Phase 1 - Cossack Victory: Khmelnytsky makes an unlikely alliance with the Crimean Tatars, and together they defeat a Polish army and capture major Ukrainian cities like Kyiv. Ukrainian peasants join the rebellion and massacre Poles and Jews. Poland loses control over much of Ukraine and Khmelnytsky is hailed as a liberator.

- Phase 2 - Treaty of Zboriv: Poland is forced to negotiate and give concessions: Cossacks gain autonomy in three provinces, the Cossack Register is increased to 40,000, the Orthodox church is given official recognition, and Polish nobles, Jews, and Catholic priests are banned from Cossack lands.

- Phase 3 - Cossack Defeat: Poland reorganizes its army, breaks the treaty, and defeats the Cossacks in the Battle of Berestechko. During the battle, Tatars betray the Cossacks and take Khmelnytsky hostage. Cossacks lose 20,000-35,000 soldiers compared to just 3,000-5,000 Polish soldiers.

- Phase 4 - Treaty of Bila Tserkva: Cossack autonomy is reduced to just one province, the Cossack Register is reduced to 20,000, the Orthodox Church loses its official recognition, and Polish nobles, Jews, and Catholic priests are allowed to return to Cossack lands.

- Phase 5 - Cossack Revenge: Cossacks ally with Tatars again and defeat a Polish army in the Battle of Batih. Cossacks spend 2 days killing 8,000 Polish prisoners of war. Cossacks retake much of Ukraine. Tatars betray the Cossacks again to prevent a total Polish defeat.

- Phase 6 - Russia Enters: Khmelnytsky swears allegiance to the Russian Tsar in exchange for protection. This agreement brings Ukraine under Russian influence and Russia declares war on Poland.

- Phase 7 - The Ruin: Khmelnytsky dies, and the Cossacks become divided and weak and argue about whether to stay with Russia or rejoin Poland. Russia betrays the Cossacks and signs the Truce of Andrusovo (1667) with Poland, dividing Ukraine in half.

For the next 100 years, from the late-1600s to the late-1700s, Cossack uprisings would continue in both Poland and Russia and both kingdoms would gradually reduce Cossack autonomy. However, Russia was more ruthless about it. Russia's approach favored mass executions and relocations, whereas Poland's approach favored removing status and privileges.

During this time, Russia also managed to exploit huge flaws in Poland's political system to block reforms and elect Kings that they preferred.

Netflix has a great series about the peak of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and the ridiculousness of Polish nobility and the Polish parliamentary system. It's called 1670.

Annexation (late 18th century)

Between 1772 and 1795, just before Poland could finally implement political reforms, it would get partitioned and annexed by Russia, Austria, and Prussia (Germany).

- Volhynia would fall under Russian rule.

- Galicia would fall under Austrian rule.

Around the same time, Russia destroyed the last independent Cossack stronghold and annexed Crimea (home of Tatars).

Competing Independence Struggles (19th century)

For around 123 years, from the late 18th century to the early 20th century, Poles and Ukrainians were both without their own countries and were forced to live under Russian and Austrian occupation with restrictions on their languages and culture. However, despite having common enemies, Ukrainians would generally not unite with Poles.

Russian-occupied Poland/Ukraine

Under Russian rule, Polish nobles got to keep their land and some political autonomy. As Polish autonomy started to get reduced and Russia interfered more in Polish affairs, Polish nobles tried to rebel against Russian rule multiple times. Polish nobles were somehow deluded with the hope that Ukrainians would join them, but most Ukrainians saw the Poles as former overlords and religiously incompatible and so did not support them. Russia crushed the Polish uprisings, punished Polish nobles with execution or exile to Siberia, encouraged Ukrainian peasants to attack Polish estates (which they gladly did), implemented heavy Russification for any Poles who remained, and tried to erase all references to Poland.

Once Poles were less of a threat, Russia turned its focus on repressing Ukrainian culture and nationalism. In 1863, the Valuev Circular heavily restricted Ukrainian-language publishing, and in 1876, the Ems Ukaz fully banned Ukrainian books, education, and performances.

Austrian-occupied Poland/Ukraine

Under Austrian rule, Polish nobles also got to keep their land but faced immediate Germanization, loss of autonomy, and reductions in rights. Austrians showed favoritism to Ukrainians to counter Polish influence, and Ukrainians were used as informants against Polish nationalist movements. When Polish nobles attempted a rebellion, Austrian officials encouraged Polish and Ukrainian peasants to kill Polish nobles.

Things changed in 1867 after Austria lost a war to Prussia. Austria needed Polish support and loyalty in order to avoid further losses, and so it switched from favoring Ukrainians to favoring Poles. Austria gave Poles autonomy and political control in Galicia, restored the use of the Polish language in schools and administration, and even gave Poles representation in the Austrian Parliament. Galicia became a Polish cultural and intellectual center and one of the most politically stable regions of Austria-Hungary.

Poles became content with the Austrians, while Ukrainians resented Polish autonomy and control and wanted independence. This Polish-Ukrainian tension would build up for decades and then explode during and after WW1.

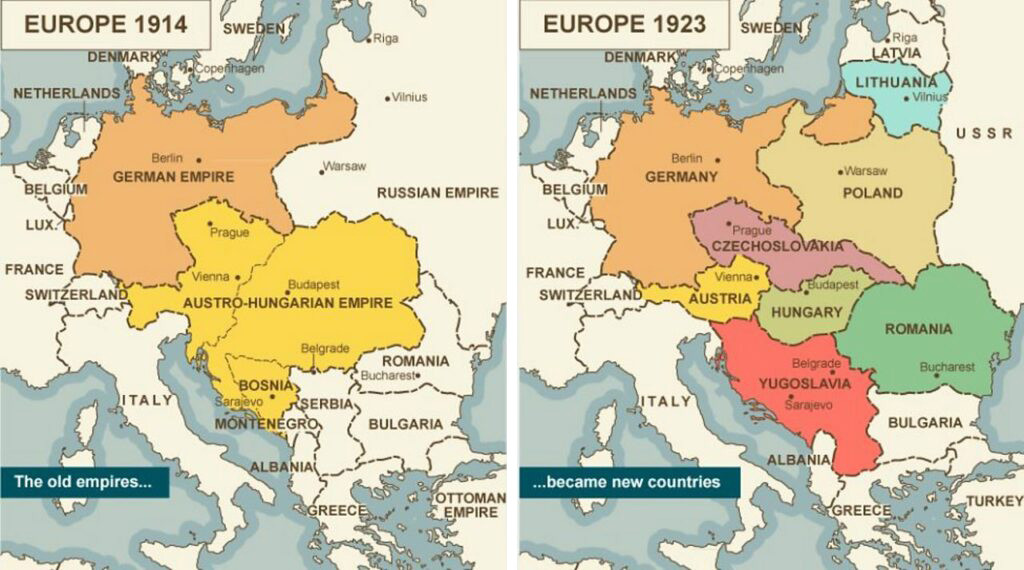

World War 1 (1914-1918)

During WW1, Polish and Ukrainian soldiers fought on both sides of the conflict due to the earlier partitions and annexations, and both hoped to use the side they were fighting for to gain independence after the war. The idea worked.

Polish-Ukrainian War (1918–1919)

After World War I and the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, both Poland and Ukraine declared independence. Ukraine immediately sent an army to take over Lviv, the Polish-majority capital of Galicia, and this started a war between the two countries.

Both Poles and Ukrainians saw Galicia as historically and culturally theirs. While Galicia did originally belong to Ukrainians ~1,000 years before WW1, they also managed to quickly lose it to the Mongols along with much of their other land. In the 14th century, Poland pushed back the Mongols, Hungarians, and Lithuanians to take control of Galicia, and ever since then, for hundreds of years, it was the Poles who developed the region and turned it into a cultural and economic capital.

In the Polish-Ukrainian War of 1918–1919, Poland managed to once again win Galicia and Volhynia and return it to Polish rule.

Alliance against Soviet Russia (1920–1921)

In 1918, Soviet Russia and the Bolsheviks started an invasion of Ukraine which then spread to Poland in 1919.

In 1920, shortly after the end of the Polish-Ukrainian War, Poland and Ukraine had to make an awkward alliance to fight back against the Bolsheviks, and Poland was able to help Ukrainians recapture their capital of Kyiv.

Unfortunately, Ukrainian leadership under Symon Petliura failed to recruit more soldiers for the Ukrainian army because Ukrainians mistrusted the alliance with Poland. The Bolsheviks then counter-attacked, retook Kyiv, and then reached Poland's capital, Warsaw.

Poland was able to quickly recruit more Polish soldiers, push back the Bolsheviks one last time, and then sign a peace treaty in 1921 to secure its independence. Meanwhile, Ukrainians were not able to fight back the Bolsheviks on their own and would continue to be under Russian control.

Some Ukrainians felt betrayed by Poland for not continuing to fight for Ukrainian independence, whereas Poland felt it did more than its fair share. Poland also felt no further obligations to Ukraine given the continued anti-Polish sentiments and hundreds of years of Ukrainian history undermining Polish independence despite us having common enemies.

Interwar Period (1922–1939)

In 1923, the League of Nations confirmed Poland's sovereignty over Eastern Galicia and it became internationally recognized.

Poland had two different policies towards Ukrainians, depending on whether they lived in Galicia or Volhynia:

- In Galicia, given how the Polish-Ukrainian War started, Poland had no tolerance for Ukrainian nationalism in Galicia and expected anyone who stayed there to assimilate to Polish culture.

- In Volhynia (Wołyń), Poland implemented "one of eastern Europe's most ambitious policies of toleration" (according to Timothy Snyder, an American historian) to prevent Soviet and Russian influence. Ukrainian schools were expanded, Ukrainian cooperatives and cultural organizations flourished, the Orthodox church was given freedom, and local Ukrainian politicians were allowed to participate in Polish governance.

Some Ukrainians respected Poland's decisions in Galicia and moved to Volhynia or the Ukrainian Soviet Republic, whereas other Ukrainians stayed to engage in separatist movements and terrorism.

The UVO (Ukrainian Military Organization), which was founded in 1920 by former Ukrainian officers, aimed to undermine Polish rule in both Galicia and Volhynia through the sabotage of infrastructure, attacks on Polish farms and businesses, and assassinations of Polish officials and moderate Ukrainian leaders.

By 1929, the OUN (Organization of Ukrainian Nationalists) replaced the UVO, which was weakened by Polish counterterrorism efforts and mass arrests. The OUN continued to escalate terrorism against Poland and received training and support from Mussolini's Fascist Italy and Hitler's Nazi Germany. The OUN viewed Nazi Germany as their main ally in their fight for Ukrainian independence.

The actions of the UVO and OUN caused Poles to lose patience with Ukrainians, and the tolerance that was shown to Ukrainians in Volhynia would be incrementally rolled back in the 1930s.

World War 2 (1939-1944)

At the start of WW2, in 1939, the Soviet Union allied with Nazi Germany to invade Poland.

- The Soviet Union captured Eastern Poland, which included Galicia and Volhynia, and they took revenge for their loss in the Polish-Soviet War.

- The OUN viewed the Soviet Union as a threat to Ukrainian independence, but nonetheless, some Ukrainians collaborated with Soviet forces to hunt down and execute Polish officials.

In 1941, Nazi Germany invaded the Soviet Union and occupied Eastern Poland. The OUN and newly formed UPA (Ukrainian Insurgent Army) helped the Nazis fight against the Soviet Red Army. Then, under Nazi rule, Ukrainians felt empowered to engage in ethnic cleansing.

- In Lviv, Ukrainians massacred around 6,000 Polish Jews.

- In Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, Ukrainians massacred between 60,000-120,000 Poles.

The massacres were known for their extreme cruelty and brutality despite most of the victims being women and children. Most Polish men were away from home during the massacre, busy fighting in WW2.

In the center, a Polish child is seen impaled on a pitchfork, resembling the Ukrainian tryzub (trident).

Ukrainians who helped protect Polish women and children were then also targeted and massacred.

Ukrainians justified the ethnic cleansing as a way to deny Poland from having any claim to the territory after the war. When the news spread to Polish soldiers about what happened to their families, they retaliated against Ukrainians using the same brutality.

In 1944, the Soviet Army made a comeback and pushed Germans out of Poland and Ukraine. The Soviet secret police (NKVD) hunted down both Polish and Ukrainian nationalists to minimize resistance to the upcoming Soviet occupation.

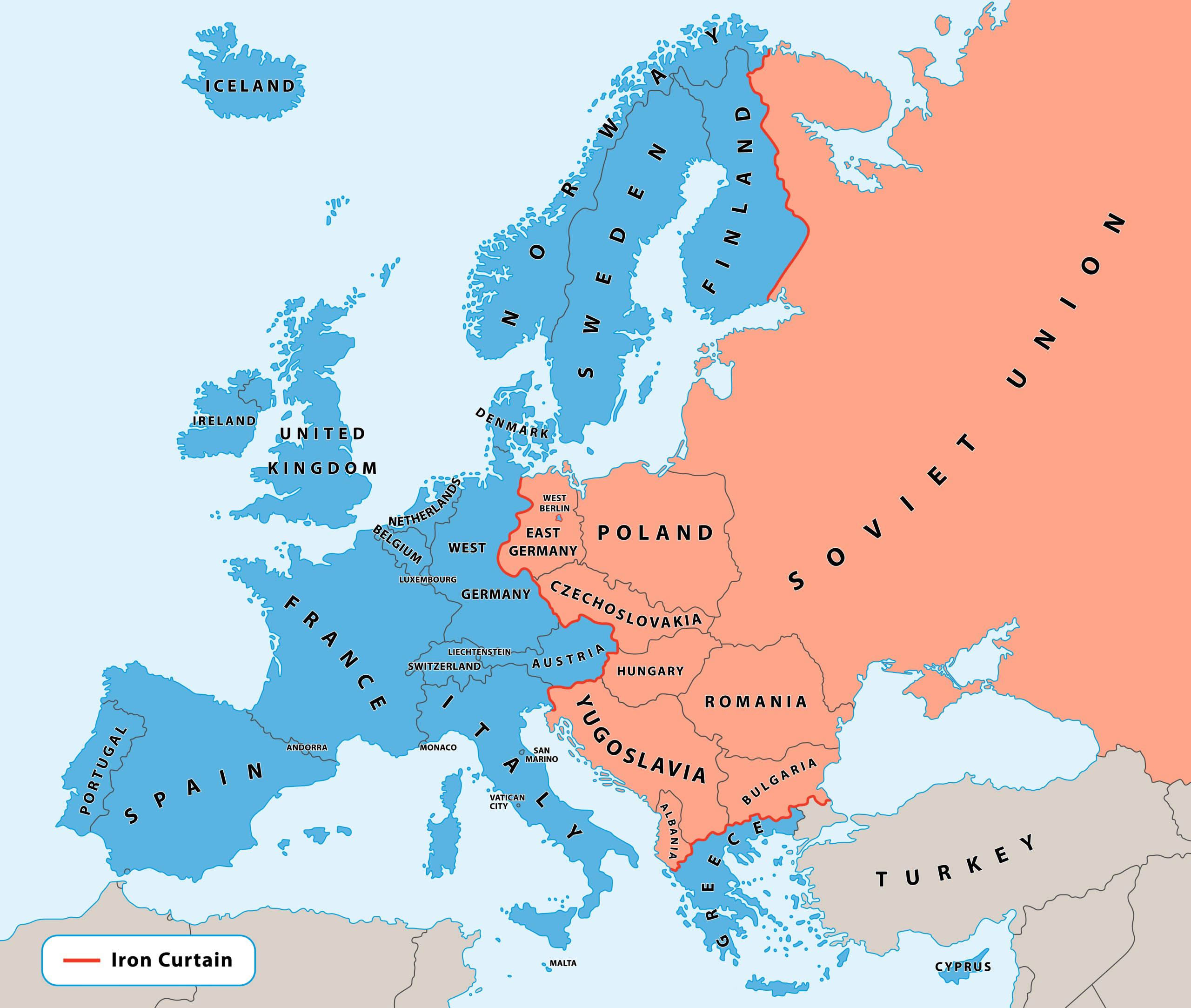

Soviet Occupation (1945–1991)

After WW2, both Poland and Ukraine once again lost their independence to Russia. Ukraine directly became part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), while Poland became a satellite state of the USSR.

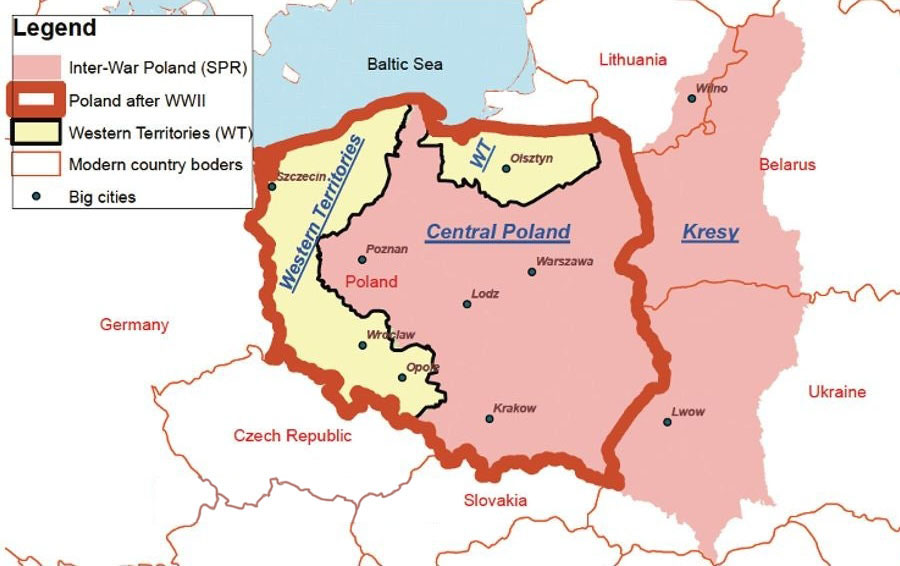

Stalin redrew national borders and gave Volhynia and Eastern Galicia to Soviet Ukraine. Soviet Poland was "compensated" for this loss by gaining back the territories that Germans annexed from Poland in the past.

Between 1944 and 1946, around 1.5 million Poles were forcibly removed from Volhynia and Eastern Galicia and resettled in the cities recovered from Germany (Wroclaw, Gdańsk, and Szczecin). Meanwhile, 500,000 Ukrainians were resettled from Soviet Poland to Soviet Ukraine to reduce ethnic tension.

Despite the generous amount of Polish land that was given to Ukraine, Ukrainians from the UPA continued to conduct terrorism and assassinations within Poland after the war.

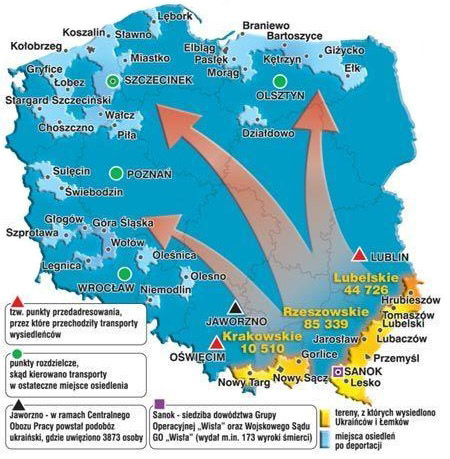

In 1947, the Soviet-Polish government forcibly resettled the 150,000 Ukrainians who remained in Poland and scattered them across Poland to better integrate them into Polish society and to weaken the UPA insurgency. This resettlement was known as Operation Vistula.

During Soviet occupation, the Soviet NKVD continued to hunt down both Polish and Ukrainian nationalists, and Soviet leadership in Moscow rewrote Polish and Ukrainian history to emphasize "Slavic brotherhood" while ignoring past conflicts.

Modern Independence & Reconciliation (1991–today)

During the collapse of the Soviet Union, both Poland (1989) and Ukraine (1991) once again declared their independence. Poland was the first country to recognize Ukraine's independence, and both countries signed treaties confirming their post-WW2 borders to avoid any more territorial disputes.

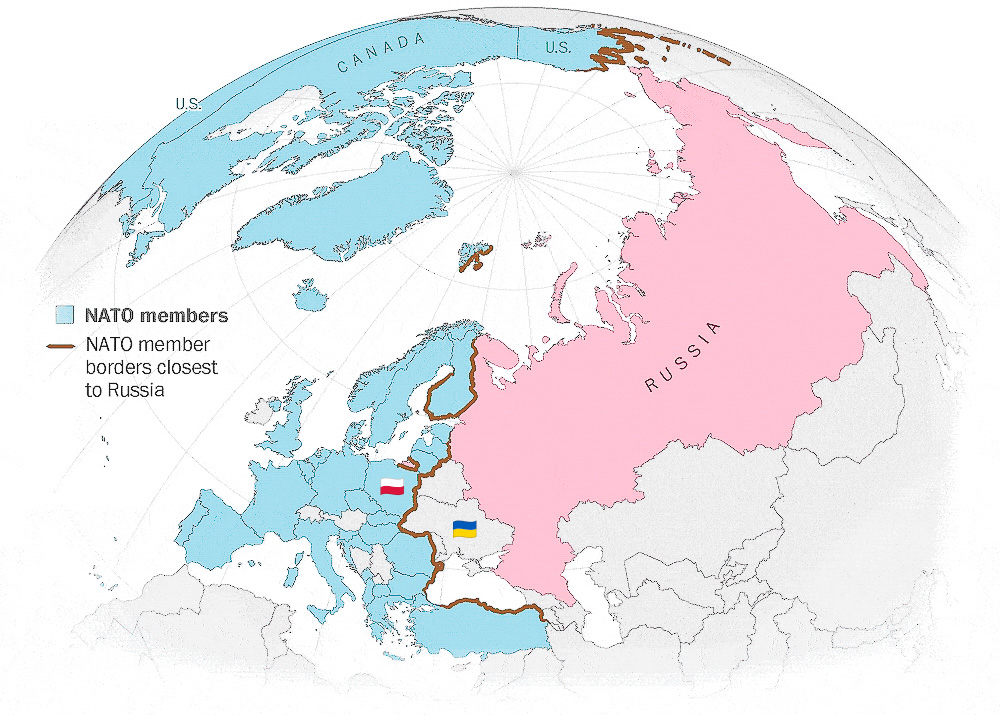

In 1999, Poland joined NATO to protect its independence from Russia. Meanwhile, Ukraine was prevented from joining for the following reasons:

- a large Russian minority in its country, particularly in the East,

- Russian political interference and economic threats,

- lack of Western support due to Ukraine's weak institutions and high level of corruption.

In the 2000s, Ukraine’s politics struggled between its pro-European and pro-Russian factions.

- The Ukrainian majority, mostly found in Western Ukraine, preferred having closer ties with Europe.

- The Russian minority, mostly found in Eastern Ukraine, preferred having closer ties with Russia.

Poland has consistently backed the Ukrainian majority that was and still is seeking independence from Russian influence. This, of course, also serves Polish interests in having a buffer state between itself and Russia.

- In 2004, Poland supported the pro-European protests in Kyiv against the Russian-backed Viktor Yanukovych. The Polish President helped mediate a peaceful solution, leading to new elections and the victory of pro-European Viktor Yushchenko.

- In 2005, Ukraine declared NATO membership as its strategic goal.

- In 2006, Poland (along with Visegrad countries) announced support for Ukraine's speedy integration into NATO.

- In 2008, Ukraine requested a NATO Membership Action Plan; Poland supported it, while Germany and France blocked it (which many believe enabled Russia's 2014 invasion).

- In 2013, Poland supported Ukraine’s Euromaidan protests against the Ukrainian president's sudden anti-EU and pro-Russian policies.

- In 2014, Russia invaded Ukraine and annexed Crimea.

- In 2016, Ukraine once again declared NATO membership as its strategic goal to protect itself.

- In 2017, Poland helped Ukrainians get visa-free travel privileges into the EU.

- In 2021, Ukraine once again requested a NATO Membership Action Plan; Poland once again supported it, while Germany and France once again blocked it (which once again enabled Russia's invasion...).

- In 2022, Russia once again invaded Ukraine. Poland welcomed millions of Ukrainian refugees, provided Ukraine with military aid and logistical support, and advocated for Ukraine in the EU parliament.

Despite all this support and collaboration, some historical diplomatic tensions remain between Poland and Ukraine—especially over the Volhynia massacre:

- Ukraine has still never formally apologized for the massacre,

- Ukraine continues to glorify those responsible (like Stepan Bandera, Roman Shukhevych, Mykola Lebed, Dmytro Klyachkivsky, and others) as national heroes with monuments and street names,

- Ukraine refuses to build a memorial at the site of the massacre, and

- Ukraine has blocked Polish historians and archaeologists from exhumations at the site. (Update: this finally got reversed in 2025).

Some Polish politicians have stated that they will block Ukraine's efforts to join the EU if progress is not made on these topics, and I agree with them on this.

In 2024, Ukraine made a diplomatic issue out of Poland trying to protect its already economically stressed farmers from cheap Ukrainian wheat exports that don't meet the same strict and expensive EU standards that Polish farmers have to follow. Zelensky publicly insulted Poland at the UN and accused it of helping Russia's war effort. This disrespect comes despite Poland already providing aid to Ukraine and making a significant economic sacrifice to take care of millions of Ukrainian refugees in its country.

Conclusion

Initially, when reading about Polish-Ukrainian history, I felt sympathetic to Ukranians and embarrassed by our Polish nobility's obsession with pushing Catholicism even though it went against our constitution. It reminded me of Christian Republicans in America who try to insist that the USA is a "Christian nation" despite the US Constitution clearly separating church from state.

However, as my reading reached more modern history, I became more frustrated with the Ukrainian side. I sadly realized that...

- Ukrainians have consistently rebelled under Polish rule even when given lots of cultural freedom and tolerance.

- Ukrainians have consistently undermined Polish independence movements even when we had larger common enemies to fight.

- Ukrainians' national heroes often had genocidal views against Poles. This makes it difficult to teach Ukrainian nationalism without also spreading anti-Polish hate.

- Ukrainians weren't shy to genocide 100,000+ Polish women and children so that they could be in a better bargaining position for redrawing borders. There was no similar precedent from Poland's side to justify this.

- Ukrainians continued insurgency against Poland even when Stalin gave Ukrainians a very generous amount of Polish land.

- Ukranians and Poles only had lasting peace with each other after we were forcefully separated and relocated by the Russians.

- Ukrainian leadership can quickly become disrespectful and ungrateful towards Poland when it doesn't get everything it wants (as seen in the recent grain dispute).

Do I still support Ukraine in its fight against Russia?

Yes, I'm still rooting for Ukraine to win! Russia was clearly in the wrong with its invasion, and it needs to be made clear to Russia that this is not ok in 21st-century Europe. No sane person wants to return to the Europe of the 20th century.

Do I still support long-term migration from Ukraine to Poland?

No, not anymore. While I do support Ukrainian refugees staying in Poland until the war is over, I don't think it's a good idea to keep a significant Ukrainian population in Poland for longer than necessary. This has never ended well for Poland in ~500 years of history. Those who want to stay should be able to demonstrate integration into Polish society.

If/when we have a real labor shortage that would require migrants, I'd rather we invite migrants from countries that haven't shown us hundreds of years of contempt. People from places like the Philippines, Goa, Brazil, Mexico, and other parts of Latin America would integrate better in Poland thanks to:

- shared Catholic beliefs and traditions,

- no history of hating Poles or Polish culture,

- no risk of insurgency due to perceived land claims from 1,000 years ago.

Comments

Please let me know below if you think I got anything wrong or missed any important events or details. Please also share if you have a more optimistic view of Polish-Ukrainian history and your reasons for it.

There is an immense amount of history that needed to be summarized for this article, and I had to strike a balance between detail vs length. Even after many cuts, it still ended up longer than I originally hoped.